Ben Ivanovas is a forced hero. He doesn’t produce or provoke any events or intrigue. Life itself forces him to fight for survival. Life itself forces this forgotten and beat-up person left alone in a foreign country without the knowledge of the local language to find his way from the bottom, showing the extraordinary temper of a real man. The man is slowly helping himself out of a dead end. Talking about himself, Ben says that the Battle of Grunwald, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, is in his blood. All the nations are mixed in the blood of this simple guy whose only exceptional quality is his will to live. This theatre production is a tribute to such a man: A pilgrim, a wanderer who survives only through his love of his mother tongue, through his astonishing will to live and his ability to stand proudly on his own feet. Watching Exile it’s difficult not to remember The Man without a Past by Aki Kaurismäki. The main character in this film managed through his troubles because he could stand alone and because of the tendency to self-sufficiency that exists in every society.

The main feature of the play is a slow transformation of the narrative into Ben’s monologues. The protagonist is not really intelligent, but he is able to understand what should be the next step. Ben uncovers the hostile world, pulling out of it the support he needs. It looks like he has a mechanism of recovery inside himself. It’s a kind of a sixth sense, a survival instinct. It’s a Robinsonade — but an East European one.

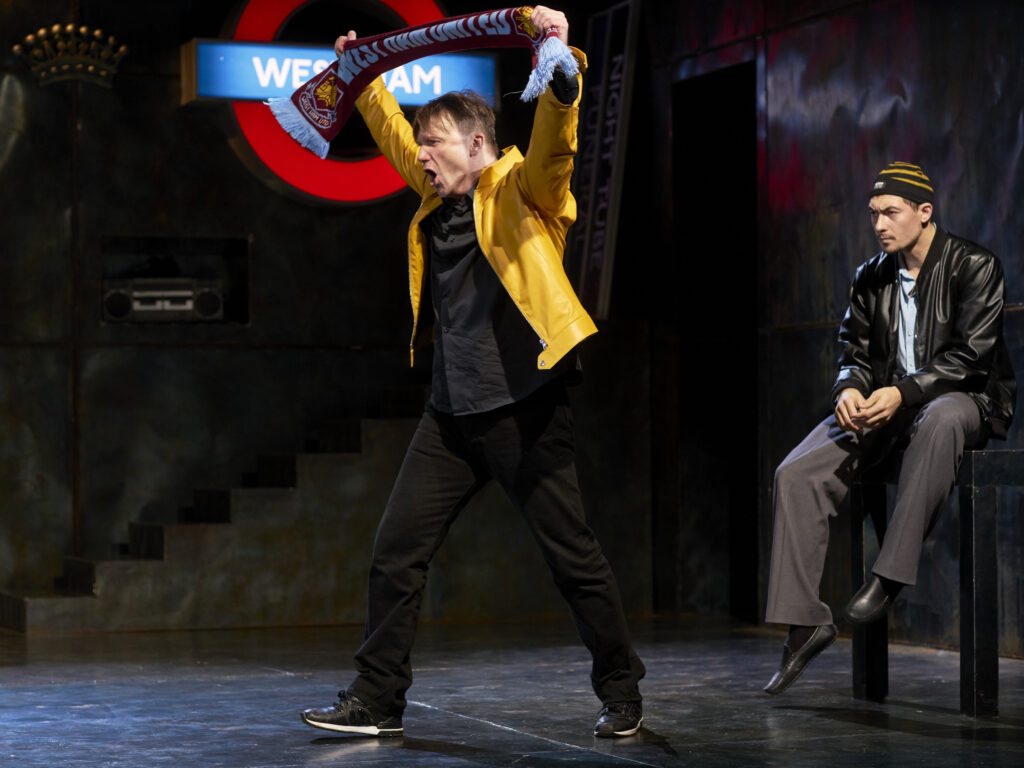

The stage is full of attributes typical of the urban landscape of London: underground stations, neon advertising, gray aesthetics of backstreets of the capital and rusty tin. The only things that change are the episode titles, exactly as the stations of the huge underground-octopus change, stations that should be mastered by Ben from Lithuania, who doesn’t want to fall into the clutches of the city. Two other attributes of the newest British style are printed on the program: Freddie Mercury equipped with the bat of Alex from A Clockwork Orange. The most interesting metamorphosis happens for Ben on the level of language. Lack of language and passion for it form a huge discomfort in the soul of a migrant. Love of the mother tongue and an inability to speak it become, in the play, almost a problem of discontent of a body that cannot be satisfied. An acquaintance Egle (played by Anastasia Dyathuck) physically jumps on Ben because she wants to fuck in Lithuanian. This language addiction is similar to a sexual one. This feeling of language, this ability to hear and to speak it while being understood is like a skin touch.

By the way the fact that dirty words in this production are replaced with normal ones creates a feeling of tongue-tied existence, of a foreign language, of the muteness of a stranger who is not at home. The way to get by censorship turns into a new interesting artistic instrument.

Before encountering Egle, Ben meets Freddy, who becomes his imaginary friend and his teacher of the new language. Freddy gives Ben a kind of new birth: Ben turns from a wet puppet into a reasonably fit buddy who has language and passion. Ben needs Freddy as a mirror: he starts believing in himself only being reflected in this wonderful music. During the culminating scene, Ben imitates Queen’s Bohemian Rhapsody, playing every note on his own, explaining it in his broken English, singing and dancing it, translating it into his peasant dialect. In Ben’s time of losing himself, of entombing his own personality, the imaginary friend Freddy helps Ben reconstruct himself, put himself together again. Ben lives for Freddy, imagines himself being Freddy, cries with him, becomes this music, and sucks the whole energy of this image into his own body as a vampire, becoming material and self-conscious again. The comical breakup with Freddy is symptomatic: It happens not only because Ben no longer needs Freddy and is disillusioned by him again and again. His idol is a gay man, born Muslim (which is unbearable for the narrow-minded). It happens also because the image of Freddy is lived out and blown off like a rubber doll.

Lithuania and Eastern Europe are interpreted by Ivaškevičius in this text as a geopolitical hole left after the fall of the Iron Curtain. The search for a better life is here the same as the search for self-identification by this coarse, ordinary guy with a European name, a simple Russian surname, and a Baltic accent. It is Grunwald who looks in all directions, speaks a lot of languages, and stays at a fork in the road. The language game in the play is more sophisticated: Ben is an eternal battlefield for Genghis Khan and Jesus Christ where no one wins.

Vyacheslav Kovalev plays the role of Ben selflessly and fearlessly. It is rare to see an actor on stage who feels himself as free as a fan during a football match. His Ben isn’t clever or really talented, but he feels his masculinity and brutality as a presence, as a kind of being here and now, establishing himself on the foreign land through his powerful and hyperemotional body. Putting on the uniform of a police officer, Ben feels himself a real Brit. The clothes make the person, not the other way around. Ben stands firmly on his own feet asserting himself through the endless reflection. This occurs not so often in this world: To analyze and to doubt all, to be disillusioned nowhere, and to be charmed by nothing.

“You still have power,” women tell Ben. Apparently exactly this idea helps the migrant conquer London, the city with no power. The power of migration is in its passion, its suffering. A migrant who is still evolving and who needs something from this life arrives at a dead city. Vyacheslav Kovalev’s Ben has a lot of fantastic boyishness, the ability to run and jump cheerfully while not being confused by himself. In the death car, we’re alive.

This production has a rare intonation for 2017: It’s about an extraordinary will to resist, the victory of a man over dead matter, and the universal breath of death.

Exile, written by Marius Ivaškevičius and directed by Mindaugas Karbauskis, premiered February 3, 2017, at the Vl. Mayakovky Theatre, Moscow.

Pavel Rudnev, «The Theatre Time»